I used to believe that reading more books would make me a better person.

This felt true in my younger days when my brain was still like a sponge, eagerly absorbing knowledge. With every page turned, I could sense myself maturing, thanks to the wisdom within those pages.

But now, as an adult, my mind feels like it’s reached its capacity.

Remembering everything is a struggle, especially when I rush through books, wanting to move on to the next one quickly. The joy of reading has turned into a burden; it's no longer the enjoyable experience it once was. I don’t feel like learning anything from those books either.

At a certain point, it struck me that, remarkable as our brains are, they have their limits. They're not designed to take and store everything forever.

So, to me now, it’s no longer about how many books I devour, but rather how deeply I comprehend, and how long I can hold onto and apply what I've gathered from those pages...

Learning approach and brain’s memory retention

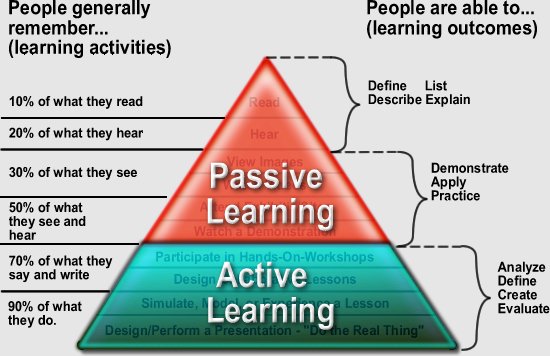

In 1969, Edgar Dale introduced what is known as the “Cone of Learning”, which outlines six levels of learning. Dale’s theory suggests that individuals retain:

10% of what they read (level 1),

20% of what they hear (level 2),

30% of what they see (level 3),

50% of what they see and hear (level 4),

70% of what they say and write (level 5), and

90% of what they do (level 6),

where levels 1-4 belong to passive learning, while levels 5-6 belong to active learning.

Around half a century later in Japan, another intellectual, Dr. Shion Kabasawa, a psychiatrist and author of dozens of books, also proposed a similar theory on how learning approaches relate to brain’s memory retention from a neuroscience perspective.

He suggests that the primary means to remember what we’ve learned for longer duration is through “doing output”, which essentially aligns with the active learning process outlined in Dale’s Cone of Learning.

When these two concepts are applied to reading, it's clear that to remember more from any book for extended period, we must shift our approach. Reading should not be a passive act of consumption, but rather an active process of engagement.

“Dialogue with book” revisited

“Dialogue with book”, a term I picked up from a speed-reading seminar, which I wrote about in my previous entry, gave me an immediate impression of an interactive approach, but I found it quite the opposite in practice.

“Dialogue with book” places heavy emphasis on speed, which turned out to be counterproductive, as it essentially reduced my interaction with a book to mere “reading”, comparable to level 1 in Dale’s Cone of Learning.

I always ended up forgetting almost everything I read... hold on, “forgetting” doesn't quite seem the right way to put it — it's more about the parts I missed because I purposely skipped many sections of the book to find answers to the questions in my mind. Of course, I also ended up forgetting the other parts I did read.

As a result, I had to reread the same book over and over again, without even realizing what I had been doing. My initial goal of saving time through this speed-reading technique ironically had caused me to consume more of it.

Now that I think of it, speed reading makes no sense to me at all. I learned the hard way that the only way to read faster is to read more and more books. I’ll write more about this on another occasion.

However, the term “dialogue with book” does sound intriguing, although it didn’t live up to its name. This made me feel a strong urge to modify it to align it more closely with what its name suggests: interaction and fun.

“Doing output”

The major flaw of “dialogue with book” is its lack of engagement, while engagement, the key element in active learning, is what enables our brain to retain information for longer period.

To make up for this shortcoming, I borrowed Dr. Kabasawa’s theory on “doing output”. His theory presents a concept that, in my opinion, does a good job in contrasting passive and active learning by employing the notions of input and output, making it easier to visualize and understand.

Input basically means consuming. It can be reading books, listening to podcasts, watching TV, scrolling through Facebook feed, and so forth. When we introduce new information, or even information we already know, to our brains, we’re said to be “doing input”.

“Doing input” is passive, as we’re receiving something from other people or from media. It corresponds with levels 1-4 in Dale's Cone of Learning.

Output, on the other hand, means creating or sharing. For example, when we discuss what we’ve read or watched with someone else, or when we write a summary of what we’ve just read, we’re essentially “doing output”.

“Doing output” is active, as we’re giving something out, either to other people or to ourselves. It matches up with levels 5-6 in Dale's Cone of Learning.

Dr. Kabasawa himself has set a good example of “doing output”, as he’s seen very active on his blog, YouTube, and Twitter.

The real dialogue

The basic idea behind “dialogue with book” was to keep questions in mind while reading, as if we were having a conversation with the book itself.

But this so-called “dialogue” turned out to be nothing more than a monologue in practice. I found myself skimming through chunks of text, hunting for answers to my questions, with no guarantee of actually finding them, let alone a satisfying one.

In the process, I realized I wasn’t actually “listening” to what the book was trying to tell me. Instead, I was too preoccupied with getting answers to my questions, overlooking many of the important messages and lessons the author intended to deliver through their book.

So, the very first step that immediately came to my mind to make this right was to flip this fake dialogue into a more genuine one.

Depending on our creativity, there are various ways we can choose to “interact” with a book. In my case, I like to imagine the book as the author themselves. This makes it easier for me to engage with it because it’s simpler to connect with people than objects.

Seeing and treating things as if they were alive is indeed my preferred approach, and I’ve written about this before. Not only does it help us build the empathy we need to truly “listen” — a crucial skill for learning new things — but it also stimulates our creativity, allowing our minds to conjure up unique ideas. All of this will certainly make the whole reading process more colorful and enjoyable.

After all, I’m certain most would agree that it's easier to converse with people than with things.

---

I should actually be continuing with the main course at this moment, explaining how the improved “dialogue with book” works in practice, but I feel a bit too tired to do so right now. Anyway, the best part is always saved for last, isn’t it?